Institutions Closures, & Experience

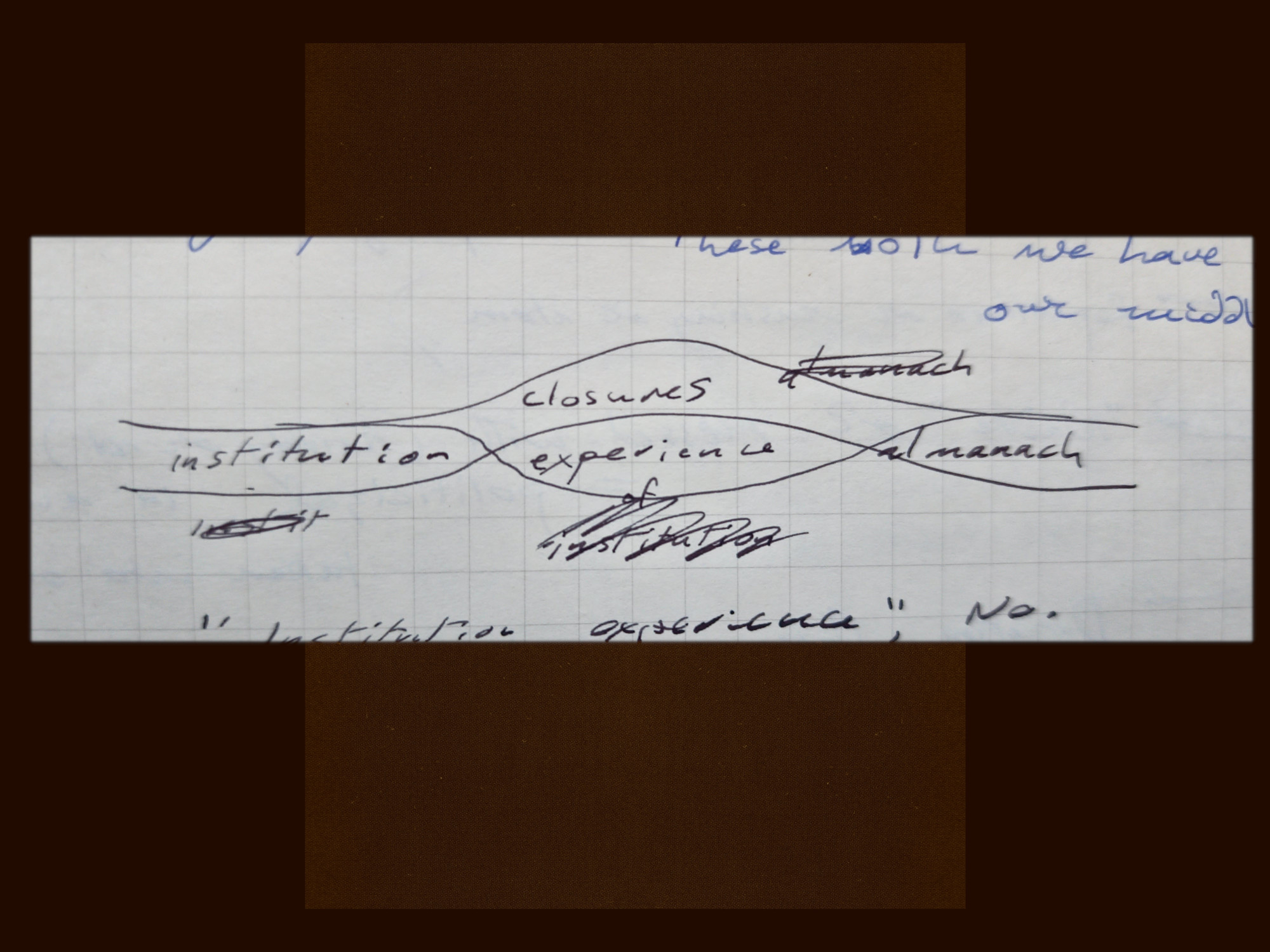

Program statement bow-tie

“Minor” Institutions

We are not talking about “the institution,” as one often names the system of authorities such as schools and museums which certify cultural production. Certification isn’t our problem. Material, terrestrial, minor institutions are our object. Not Danto’s but Saint-Just’s, Tosquelles’s and Deligny’s.

Like a corkboard in a bookshop which happens to be the most queer-friendly space within 100 miles. Like a prix libre cantine in defunct café. Like a department whose power as a gathering place outdoes even its professors’ offerings and gives their teaching the hungriest ears. Or the everyday presence in the student lounge of those who fought for academic sanctuary 20 years ago. And a farm in the mountains where the nonverbal and the speaking learn to live together.

Samuel Delany’s cinemas, the porno theatres of Times Square pre-1995, belong on this list. Their closure compelled Delany to document them not as facts but as practices, collective practices which exceeded the individuals who made use of the spaces which these practices sustained. His twinned essay Times Square Red, Times Square Blue works to save and pass on the experience of this institution—not his experience of it but the weathered knowledge that was in the institution itself. Delany does not write from loss, but towards a future.

What was there was a complex of interlocking systems and subsystems. Precisely at the level where the public could avail itself of the neighborhood, some of those subsystems were surprisingly beneficent—beneficent in ways that will be lost permanently unless people report on their own context and experience with those subsystems.

The polemical passion here is forward-looking, not nostalgic, however respectful it is of a past we may find useful for grounding future possibilities.

Samuel Delany in Times Square Red, Times Square Blue

Hope is a material thing. Hope is in the hands. Maniability, malleability. Our hands aren’t empty even now. The bow tie of the closure and experience of institutions, which Obiits.org sets as its program, is a hand-me-down from Delany.

The closures are a fact. What follows will present its siblings stakes, that is, what effect institutions and experience are hoped to have.

Society

and Community

Gap

Hope

“Institutions” minds a gap left unworked by two customary ways of thinking about human collectivity: society and community. In place of a definition, we will present it by contrast, first to society, then to community. This procedure gives the stakes of the concept which a descriptive definition would leave out.

Sociology’s facts are “total.” Kinship structures are an example, relations of production too; just as you can’t take part of the social contract and leave the rest. Between institutions and society, that is, the difference is one of scale. Society is all or nothing, and there’s only one of it, where institutions are something smaller and there are many of them.

Institutions and community have something in common. Community, too, is charged by society’s all or nothing and the need to break free from the forced choice between totality or atomization with which it presents us. It names, at the same time, a historical disaster. Community is what enclosure, colonization, nation-building, and competition have destroyed.

These stakes do not mean nostalgia. Community’s critical function lies in affirming a viable middle. In which we can live together with some autonomy. A viable middle, because hope and the making of hope are at stake. This much, community and institutions have in common.

Community as an ideal has important things to teach, but two of its lessons must be unlearned. 1) As an image of presence, proximity and concrete relationships opposed to quantity, delocalization and forced migration, it seem to tell a story of a natural human gregariousness which artifice can only dismember. But by rejecting artifice, one relegates human agency to the artificial fields of law and merchandise, leaving only a very poor conceptual apparatus to think human making in their own communal relations. There are other arts to make bonds beyond exchange and legality. The near and the home are themselves artifacts of human making. And they are made in many ways. That is, to paraphrase Spinoza, we don’t yet know what home is capable of.

2) The loss of a community is the loss of a world, but not the loss of all collectivity. Within a community’s one, many are humming, relations and multiplicities which survive it. A damaged life and a torn community remain social. A social rubble, perhaps. But there’s a world of difference between beginning again from nothing and trying to work with the collectivities that remain.

The social totality we live in is dead-set on atomization. Austerity is always first of all the impoverishment of association. Communities are unbound; the stocking has come undone; many of us grew up altogether without them. But it would be a mistake to believe that we are left with just atoms.

Institutions are many. One passes through fifty of them with every step one takes.

The concept of institutions can make this dimension of social facts into something we can talk about. Facts which are not untouchable hoverings in the structure, all-or-nothings of joining or leaving society or idealized communities receding into nature and modelled on love.

Portrait

Attributes and Gradients

Institutions are many, institutions differ. Instead of a definition, we’ll list the differences it holds. Gradients, sometimes disjunctions.

When one recognizes its gradients, smaller and larger, inchoate and recognizable, unfigured and explicit, dictatorial and collective, one develops an eye. One sees them. One sees that they are everywhere. And at the same time that they are rare.

A place can make an institution, and an institution can make a place.

Some institutions can render distances imaginable, make distances interesting, viable.

Some institutions live in proximity, and require first-person, face-to-face assembly. In what environment? How porous?

An institution is not just a with and a many. A with is also a between. There is distance here too. Do we need to step back to see one another’s face? Suppose between us a table. What is on it? What words are between us? Who else is at the table? Who will visit, who will tell us their news?

Institutions permit ephemeralities: visitors, guests. Encounters, diagonals.

Some institutions show solidarity to others outside them.

Some exist above all to give a place and peers to researchers to whom no such public has been offered. Their association is diagonal. “Interdisciplinarity” is a program of hospitality. (Favret-Saada in Vacarme 28: “J’ai trouvé dans l’expérience, les écrits, et le milieu analytiques un appui que mes collègues ethnologues me refusaient. / In the psychoanalytic experience, writings, and milieu, I found the support which my colleagues in ethnography refused me.”)

“Membership” is only one sort of belonging. Which itself names a wild variety of genres of status and belonging and relationship. Maybe there are eaters and cookers, or talkers and translators. Maybe some of us can speak, and some of us are nonverbal. Difference doesn’t mean valuing one over the other. Maybe we have different experiences, different things to teach. Intergenerationally. (Alex Martinis Roe on Affidamento: “Indeed in naming it, and practicing it intentionally, they [the Milan collective] created a radical ethics of difference, where this entrustment to the other is actually an entrustment to her difference—in other words, a radical openness and commitment to another’s irreducible difference”.)

Gradient: Institutions can be more or less self-regarding, that is, contain their interest in themselves. Or desiring, working on something else. This something else could be in themselves. Or this something else could be something other, even something other than human.

Institutions can be narcissistic, which is not the same as being self-regarding.

To the prepositions “with” and “between”, let’s add “amidst.” The Rabbis said that institutions (of two in study, of three at dinner, of ten at temple) share amidst themselves a word of learning, or do not. With this learning-word comes a kind of spiritual presence, and absent it, something ugly. (Pirkei Avoth 3:2, 3:3, 3:6.)

The concept of institution contains something disjunctive. They can form little dictators, little servants. Or they can produce something one would describe as collective.

Routines and regularities broaden participation, and not because of inertia. Improvisation and informality narrow to active clusters.

An institution sometimes depends on a single individual. More or less; this is a gradient. — As one says, “She’s an institution!”

Like Mrs. Ramsey (To the Lighthouse) or Jan Ritsema (PAF) or Irma (Le Balcon). Mrs. Ramsey is balancing a dinner table/tableau while Lily Briscoe is composing her own institution on a surrogate easel: move the tree a little to the left, ah, that’s the solution!

When an individual holds an institution together, it isn’t because they are its Founder, as if they swept atoms into a bag. Their “materials” (which is a very wrong word) are active. This activity involves different degrees of dependence and transference. Managing this transference and dependence can mean manipulation (said here without judgment).

What kind of troubles does an institution have? What kind of mediation is it using to respond?

Institutions are lost and made but above all kept, reproduced, and mutated.

A friend adds: “I’m reminded of Derrida’s speech at the celebration of the 20th anniversary of the Collège International de Philosophie in 2003, where he said that longevity is not in itself a merit, and that beyond ‘celebrating,’ it is also essential to reflect on the compromises under which an institution survives its possible closure. The closure of an institution, like the death of a person, is an essential moment of its life and after-life.” (Thanks, Gabriel! Source.)

We are not sticks in a bundle, but a tension, an arc and a chord.

An bow can lose its tension.

The makers of an institution may have chosen to join it. They may not have had a choice. The autistic children of Deligny’s farm in the Cévennes have left hospitals with caged windows. The organization of the women of the prison ward in Evin Prison did not choose to be in the ward, but did resist.

The question is never really, “Is X an institution?” Both have something to teach and questions to be asked.

Institutions make habits. Habits are capacities are knowledge.

How does a newcomer find their feet?

How does an institution know about itself? How does it articulate what it knows about itself? Stories? Examples? Rules? Principles? Hadiths? Koans? Or something else entirely.

An institution learns. How is this learning kept, recorded, and passed on?

Passed on: to whom? To others on another continent. To others a decade later. Whatever’s written is a post-card, no envelope. The riddle is how to open a post-card.

An institution learns and teaches, and it studies, and it studies history too. How does it read history, in order to be able to learn something from history that concerns it?

Founding an Institution,

Making an Institution,

What an Institution

Knows,

and Us.

Experience

At a moment when so many institutions have disappeared, one comes to reflect on the conditions of their founding. Certain children, author included, dreamed in manifestos and grew up wishing for another way of being together. But founding gives a warped perspective on the making of institutions.

Our need for a founding act, in spite of the fact that one has never been observed nor taken place, testifies to a collective desire for dependence, to wishing it were necessary to serve One and subjugate Many. (See Étienne de la Boétie’s Discourse on Voluntary Servitude, or, The Against-One [Contr’Un], ~1546.) Which is not Obiits’ subject, apart in inviting the contrary gesture.

Institutions make institutions. They make themselves and, unmaking, they make themselves other, they join, they diagonalize. Each time a risk. Each time, their act is something they add, on no foundation, but a hypothesis, a wager, in the creativity of duration and the invention of reproduction. The making of institutions is not in their beginning, but in their middle, in the creativity of duration and the invention of reproduction.

This creativity is learning. An institution’s self-knowledge is the midstride know-how of this creative, learning middle. Experience names what is learned midstride and outdoors. How do they hand on what they learn? How can we learn from them? What discourse is adequate? To do so requires us to unlearn the reflex to foundations. We do not know the “recipe” for an institution by reading its principles and laws, even when we ourselves wrote them.

What does that leave us? An aporia. The aporia of the writing of experience is also a genre, which Montaigne named the essay. Rather than presuming the homogeneity of our genre to the birth of the thing itself, as legal restitutions of legal beginnings pretend to do, our form names the tension between itself and the knowledge named. Our experience always exceeds its beginnings and all the traditions of its matter and environment. If our knowledge becomes, again, transmissible, legible, this too will be our collective making, even without intention.

The form of teaching might be a case, like Freud’s five studies, which methodologically chose to pass on more than they could analyze. It might be a writing like Samuel Delany’s essays—truly essays—which give us an example. Rich in details to the point of exceeding any thesis he might affirm, and by this excess become not only a claim but a source. Or simply description, which Bojana Cvejić’s methodology of ekphrasis brings in such excess of argument that it seems to step out of the page. And this is the case even for the verbless among us, whose lignes d’erre, wander-lines, transmit the collective know-how of human beings both speaking and verbless making a life together. Speaking and verbless, we are learning creatures and teaching ones.

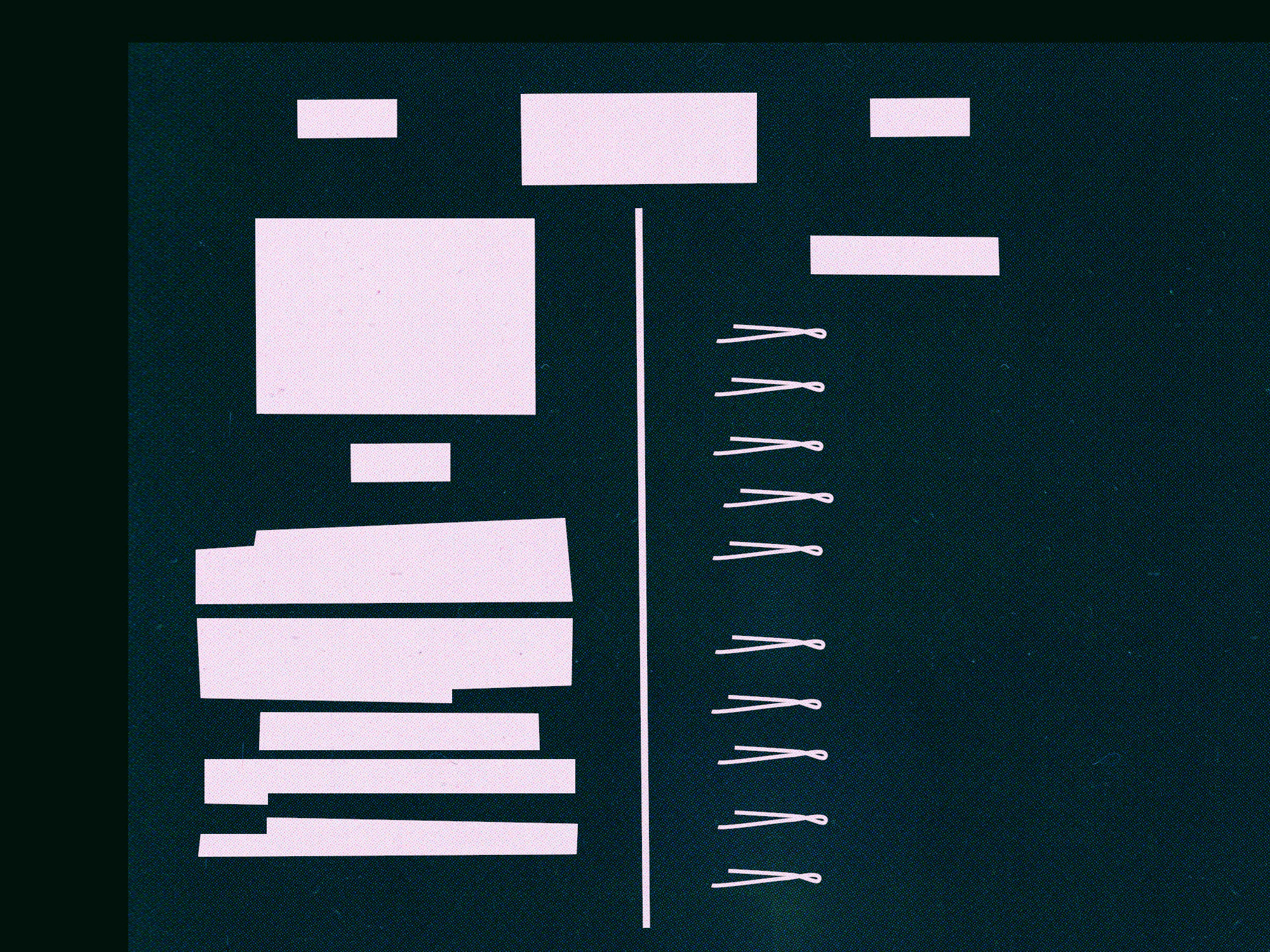

Obiits.org is a practical proposition. Bulletin of closures in the right column; quarterly profiles in the left, which have, for vocation, the articulation and transmission of the experience of an institution. These ventures will be, of necessity, essays. It must be left to the essayist themselves to try for a form adequate to their teachers.

Right column: a bulletin of closures. Left, written in hope.

⚘

(Published January 22, 2026, revised February 20. Write to crew ɐ obiits ◊ org with amendments and additions or questions and reactions. For December’s draft, [click here].)

If you would, please communicate your reactions, questions and associations to crew ɐ obiits ◊ org; please also flag passages that are unintelligible.